Why Are Countries Trying to Secure Yttrium Supply?

Some basic facts about a little known rare-earth element

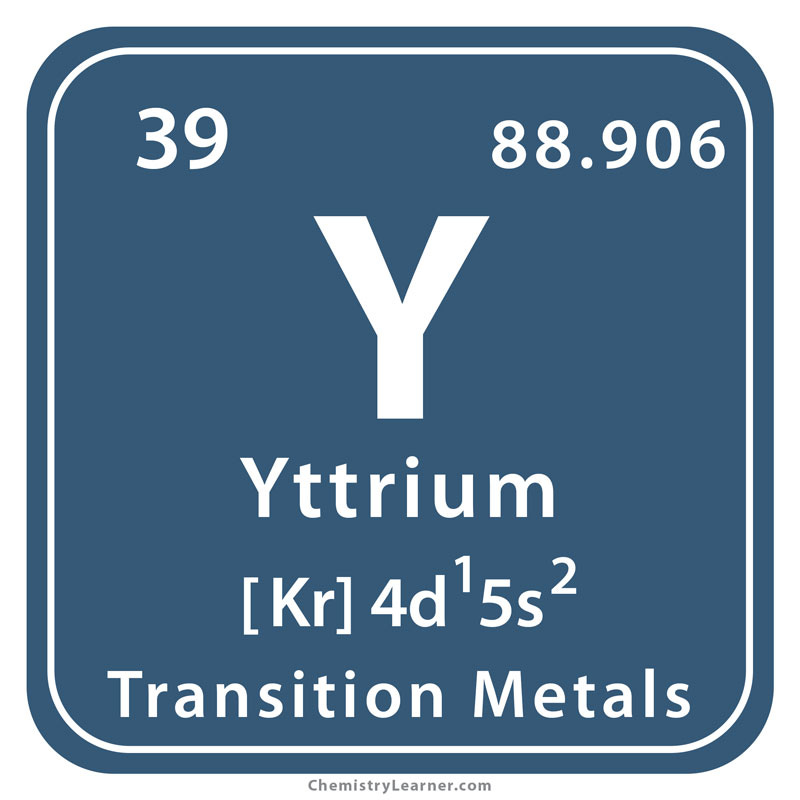

Yttrium, a silvery metal little known outside the industries that use it, has quietly become one of the most watched critical minerals of 2025. The element, atomic number 39, belongs to the rare-earth group. It is found in the same ores as better-known metals such as neodymium, but separating and refining it is expensive and complex. It has the following uses:

Heat-resistant coatings for aircraft engines and gas turbines

Bright phosphors in LED lighting and smartphone displays

High-strength permanent magnets for electric vehicles and wind turbines

Treatment of inoperable liver cancers (specifically, Yttrium-90 isotopes)

Components in military lasers, radar and the F-35 fighter jet

Demand for yttrium is rising 5–8% a year, driven by the shift to electric vehicles, renewable energy and modern defence systems.

Who controls yttrium production?

China mines about 60% of the world’s rare earths and refines more than 90% of all yttrium. The two largest producers are state-supported companies: China Rare Earth Group and China Northern Rare Earth Group. Outside China, meaningful supply comes from only two companies:

Lynas Rare Earths (Australia)

MP Materials (United States, Mountain Pass mine)

Much of these non-Chinese producers’ output is still sent to China for final processing. China’s grip on supply of the refined metal is what governments are concerned about. When a single country can control almost the entire supply of a metal needed for both civilian technologies and advanced weapons, it creates a clear security risk. In April 2025, Beijing imposed export controls on yttrium and six other heavy rare earths in response to new US tariffs. Prices rose sharply within weeks and several Western manufacturers (who have yttrium as an input material) were forced to cut production. The episode reminded policymakers of China’s 2010 rare-earth embargo against Japan.

The global response so far includes:

The United States committing hundreds of millions of dollars to new refining plants and strategic stockpiles;

Mobilisation of The European Union’s Critical Raw Materials Act, aiming for at least 10% domestic or allied supply by 2030;

Japan and South Korea expanding recycling programmes and signing long-term contracts in Vietnam and Africa;

Australia and Canada fast-tracking new mines and offering incentives under “friend-shoring” partnerships (buying from allies instead of lowest cost producers);

But for now, China has the bargaining chips.

Building independent supply chains will take years and cost billions of dollars. Until then, yttrium stands as a stark example of how critical minerals have moved from the margins of trade policy to the centre of national security.